1969 NDT - Harvard vs. Houston

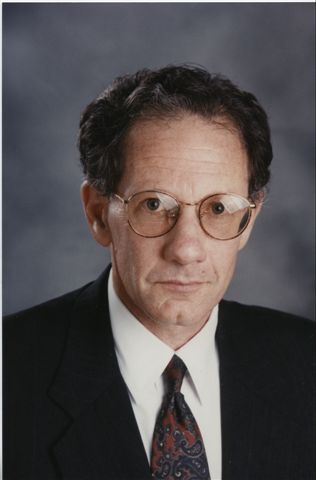

By Joel S. Perwin

Mr. Perwin's law firm specializes in appellate law, Miami, Florida

In the final round of the 1969 national tournament at Northern Illinois University, my partner Rich Lewis, a freshman phenom -- to this day one of the most charismatic speakers I have ever heard -- walked to the podium in an auditorium filled with the best debaters in the country, and said: "Frankly, I want my mother."

The finals that year paired the two "best" teams in the country on paper--the University of Houston (senior David Seikel and junior Mike Miller) and Harvard (I was a junior). Houston had won an unprecedented number of tournaments; Rich and I, coached by Larry Tribe, had won many of the others. Going into the finals, we were 3-3 against each other.

The finals that year paired the two "best" teams in the country on paper--the University of Houston (senior David Seikel and junior Mike Miller) and Harvard (I was a junior). Houston had won an unprecedented number of tournaments; Rich and I, coached by Larry Tribe, had won many of the others. Going into the finals, we were 3-3 against each other.

Reading Judge Phillip Hubbart's recollection of winning the 1957 tournament brought back a flood of memories of the '69 tournament, and inspired me to write them down. Although my recollection has been refreshed by the transcript of the final round, which is published as an appendix in the Third Edition of Argumentation and Debate by Austin Freely, and although the NDT website provides the elimination-round pairings and results, I'm sure I've glorified the experience in the interim of 35 years. To those who may remember it differently, I apologize.

The topic that year was: Resolved, that executive control of United States foreign policy should be significantly curtailed. Not surprisingly at that time, many cases argued against the war in Vietnam. Our case during the first semester argued for the abolition of CIA covert operations. By mid-year, everyone had caught on to its weaknesses, and we switched to a less exciting claim that executive foreign policy failures were the product of bureaucratic inertia and incompetence. Our bureaucracy case took us through most of the second semester, until it too began to crumble. In the hiatus before the Nationals, after much discussion, Larry, Rich and I decided to rework the CIA case, and we spent many hours improving it. At the same time, as we learned later, Houston was developing a devastating assault on the old bureaucracy case.

Going into the tournament, we had beaten Houston 3 out of 5 times. We met in the preliminary rounds with Houston on the affirmative, and Houston won. That pairing assured us the affirmative if we met Houston in the elimination rounds, which I remember thinking was a great advantage. Rich was more concerned about the weaknesses in both cases, and notwithstanding the advantage of having the last word, he remembers that our plan for the elimination rounds was to pick the negative. As it turned out we didn't get the choice; we lost every flip of the coin.

The word spread quickly that we were using the CIA case, and we told Dave and Mike that we had significantly changed the bureaucracy case, and were holding it back until the elimination rounds (we lied). At the end of the preliminaries, both teams were 6-2; David Seikel was best speaker; and I was second, as Larry Tribe had been, also as a junior, in winning the nationals for Harvard in 1961 (we considered this portentous). Thankfully the two teams were in different brackets.

Our opponents chose the negative in the first three elimination rounds. The octofinals (5-0 against Redlands, California) and the quarterfinals (3-2 against Oklahoma State) were challenging, and we were lucky to make it to the semis, while Houston was breezing against Albion and Denver 5-0 and 4-1. Still using the CIA case, we told Dave and Mike that we were holding back the bureaucracy case as long as possible (we lied again).

After the lunch break, we were scheduled to debate Loyola, California on the affirmative, and learned that Loyola was caucusing not only with the Redlands team which we had debated in the octofinals, but with all of the other California teams, pooling evidence and arguments against the revised CIA case, which Redlands had studied at close range only a few hours earlier. Larry, Rich and I obsessed about this, and decided that we might be able to throw Loyola off its game by switching back to the old bureaucracy case. The problem was that we hadn't looked at it in over a month; the first affirmative speech and the evidence were buried somewhere--in the files and in our minds. It was very risky, and the debate was not one of our best. We actually had the first affirmative's pages out of order, and Rich had to stop in the middle to find his place. When it was over we didn't feel the usual exhilaration. We were drained, and worried. Very quickly the word got around that the four ballots in were 2-2, while Northwestern Coach David Zarefsky sat for a full half hour reviewing his flow chart (a lot of fun for the debaters). Finally his vote put us in the finals. Houston beat UCLA in the other semifinal 4-1.

Of course the switch in cases set us up perfectly. As we walked over to the auditorium, either Dave or Mike said that he guessed we couldn't wait any longer to bring out our real case, and Rich and I nodded grimly. At its table on the stage, the Houston team set up two steel file drawers (no computers then) devoted solely to Harvard, containing special colored file cards (blue, I think), and each debater had a notebook outlining his arguments against our bureaucracy case. Houston was primed and loaded.

As the debate began, Larry and Houston Coach Bill English went out for a drink. At some point Larry mentioned that we were using the CIA case. Bill paused, looked over, and said: "Then you're going to win."

After Rich had pleaded for his mother, our first affirmative began with a quote from Hans Christian Andersen: "All the people who lined the streets began to cry, 'Just look at the Emperor's new clothes. How beautiful they are.' Then suddenly a little child piped up, 'But the Emperor has no clothes on. He has no clothes on at all.'" The speech continued: "In 1947 the United States created the Central Intelligence Agency, and donned the cloak of secrecy to pursue communism. Experience has proven the cloak we donned was nothing more than the Emperor's new clothes, hiding far less than we had long pretended and exposing America to peril".

I looked over at Dave and Mike, who were too busy to disguise their reaction. The two file cabinets and the notebooks were swept off the table, as both debaters dove into their other files, searching for the evidence and searching their memories for the arguments, while they tried to listen for the changes in our case. Houston's best moment was Mike Miller's classy opening to his first negative: "Frankly, I wish I was debating Rich's mother." Everything which followed was pretty-much anti-climax. Although Dave and Mike were veterans, ably regrouped, and rose to the occasion, this wasn't the Houston team which had dominated the Circuit all year. As the debate ended Rich leaned over and said "Five two, for us." The vote was 5-2.

After the finals, the debaters were driven back to the hotel in buses. I have a vivid picture in my mind of Rich, Larry and I sitting in the back row of one of them holding the trophy, exhausted, trying not to smile too broadly, while everybody looked at us.

Over the Summer I fantasized about winning again my senior year, and Best Speaker too. But I didn't go back to the Nationals. Rich and I started out in the fall, debating revenue sharing, and we were winning everything, including debates we had no business winning. After four tournaments we had won three and lost the finals in the fourth. Rich turned to me one day and said "Joel, why are we doing this?" He was right. In that moment I walked away, after three years of debating in high school and three years in college, and never looked back. I was delighted that Mike Miller won Best Speaker in the 1970 tournament, although Houston lost in the Semis. I moved on to other things. But it was a great run.

“Rich Lewis, Laurence Tribe and